‘Mutual consent,’ not US threat behind China, ASEAN effort towards SCS ‘code of conduct’

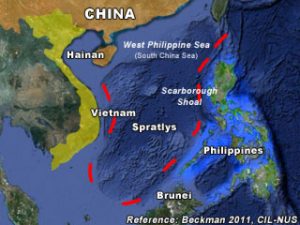

THERE is not a shred of evidence that the effort by China to reach an accord with the members of the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) on the ‘Code of Conduct’ (COC) pertaining to the South China Sea (West Philippine Sea) is to “avoid “aggressive engagement” with US Imperialism.

While there are tons of evidence that the United States has always been the “aggressor” state in its dealings with other countries, the claim by an unnamed “senior diplomat from a Southeast Asian country” quoted in an article by known US apologist, Manuel Mogato, last September 14, 2020 at the Philippine Star, that China now wants the COC signed to avoid “aggressive engagement” with US Imperialism is another work of fiction passed off as “political analysis.”

Mogato’s claim to fame is his winning the ‘Pulitzer Prize’ in 2018 for reporting the Duterte administration’s ‘War on Drugs’ for newswire agency, Reuters, which was slanted to suit the anti-Duterte narrative of the global media.

And if on Pres. Duterte’s war on illegal drugs where Mogato consciously took the point of view of critics that earned him plaudits from Reuter’s foreign bosses and foreign audience, Mogato, this time, consciously took the line of the US State Department to please Washington and other foreign powers determined to drive a wedge between China, the Philippines and ASEAN. Mogato simply ignored the facts of the SCS-COC issue.

More importantly, the article is trying to hide the fact that American bellicosity, represented by Pres. Donald Trump and Pompeo, is closely tied to the November US presidential election; just like his predecessors (Reagan in Central America, Bush in Kuwait and Iraq, Clinton in the Balkans), Pres. Trump is using the old fascist trick of “waving the flag of patriotism,” this time, against the purported “bellicosity” of China, to rally the American voters behind Trump’s candidacy.

What are the facts?

Contrary to the impression the USG (US Government) wants to create that the issue of the COC is of recent vintage, the issue of having a COC for the SCS was first raised in 1992—by the Philippines— at a meeting of ASEAN foreign ministers, during the first month of the Estrada administration.

Subsequently, the ASEAN countries adopted the ‘South China Sea Declaration’ based on the Philippines’ call for the creation of a ‘South China Sea Code of Conduct’ (SCS-COC).

In response, China proposed—and the ASEAN agreed—for the establishment of a China-ASEAN working group for COC consultation.

China worked vigorously with ASEAN countries on the COC. But parties disagreed on many things like the language, nature and geographical coverage of the document, joint military exercises and fishing activities in disputed waters, among others.

Nevertheless, during a meeting of the ASEAN and China in Cambodia on November 4, 2002, a compromise was reached when they signed the ‘Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea’ (DOC). Signing for the Philippines was then foreign secretary, Blas F. Ople and for China, Wang Yi, the current foreign minister of China.

The importance of the DOC is over the fact that it is the first political document signed by China and the ASEAN countries on the South China Sea, a milestone in their collective effort to maintain peace and stability in the South China Sea and to control and manage possible crises in the region.

In July 2011, China and ASEAN reached the “Guideline for the Implementation of the DOC,” and in September 2013, a “joint working group for DOC implementation also held consultations on the Philippines’ 1992 proposal for the creation of the COC.

Another milestone was reached in August 2017 when China and ASEAN finally agreed on a “framework text,” or the “working document” on their COC talks.

The COC is an upgraded version of the DOC. They are closely related and cannot be separated from one another.

Article 10 of the DOC provides that concluding parties reaffirm their commitment to a COC aimed at furthering peace and stability in the region on the basis of consensus.

President Duterte and Pres. Xi Jinping are “co-chairs” on the COC discussion and both want the COC signed by next year or before Pres. Duterte steps down from office.

If things go well, China and ASEAN are to meet again this coming November—the month of the US election– to agree on the final text of the COC while solving the tricky issue of whether the COC should have “legal teeth” (legally binding).

Or, would it just be, like the 2002 DOC, another political document that can be “sabotaged” by outside forces like US Imperialism or the recklessness of ASEAN members like the Philippines when it brought the SCS issue before the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in 2013?

Thus, from the narration of facts, it is clear that the present effort by ASEAN and China to sign a COC in the SCS is on the basis of their mutual consent to resolve the issue peacefully; it has nothing to do with US “aggressiveness” or its belated concern for ASEAN interest in the SCS.