To pretend an appreciation for this contrived drama will be more difficult than completing a dissertation in astro-physics.

Still, my grudging admiration for the marketing savvy behind this pseudo-documentary, which rises to the level of an extended shampoo commercial.

But after images of corporate glitz and glamour and international public speaking tours all fade, this is really what we get —

the persecuted heroine — the media Joan of Arc of the digital age —

never spent a day in a prison cell,

never endured a second in a torture chamber,

was never banned from leaving the country,

was never banned from speaking against the government

— in her monumental struggle for free speech in this blighted country.

The movie shows her getting into her luxury SUV with media in hot pursuit. Right, that was life-threatening.

The scenes vividly capture her difficulties figuring out the best wardrobe for an event. Of course, that was torture. The real climax of the movie.

And yes, she suffered the inconvenience of posting bail for tax evasion, which qualifies her for martyrdom.

You count all these and they sum up to what she calls “a thousand cuts.”

Now we know why she proclaims reporting in the Philippines is like being in a “war zone.”

Contrast her painful sacrifices to the petty inconveniences of the following lesser media mortals:

Abraham “Ditto” Sarmiento Jr.

Editor-in-chief of the Philippine Collegian, published articles and editorials critical of the Marcos regime. Wrote the famous line: “Kung hindi tayo kikilos, sino ang kikilos? Kung di tayo kikibo, sino ang kikibo? Kung hindi ngayon, kailan pa?” Arrested in 1976 and jailed for more than 6 months in a Camp Crame cell where the doors and windows were reportedly completely sealed.

While he was eventually released, his asthma had reportedly become worse during the detention. He died more than a year after his release. He was 27.

Jose “Joe” Burgos Jr.

Founder of the newspapers WE Forum, Malaya, and Tinig ng Masa—the alternative press during the Marcos Martial Law.

In December 1982, after publishing articles on the fake war medals of Marcos, his newspaper WE Forum was raided and closed, while he was arrested by the dreaded Metrocom. He spent two weeks in jail.

Maximo Soliven

The Senate tribute to him reads:

”When the late President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, Soliven was arrested at two o’clock in the morning of September 23,1972. He was jailed, then released on probation after three months, and was banned from leaving the capital for three years, and from leaving the country and from writing for seven years.”

Ditto, Joe and Max are yet to be honored with a foreign-funded indie film.

Of course, compared to Ressa who deserves an encyclopedic account of her heroics, Ditto, Joe and Max are mere footnotes in the annals of the Philippine free press. Apparently, they did not do enough to merit one square inch of a Time Magazine cover.

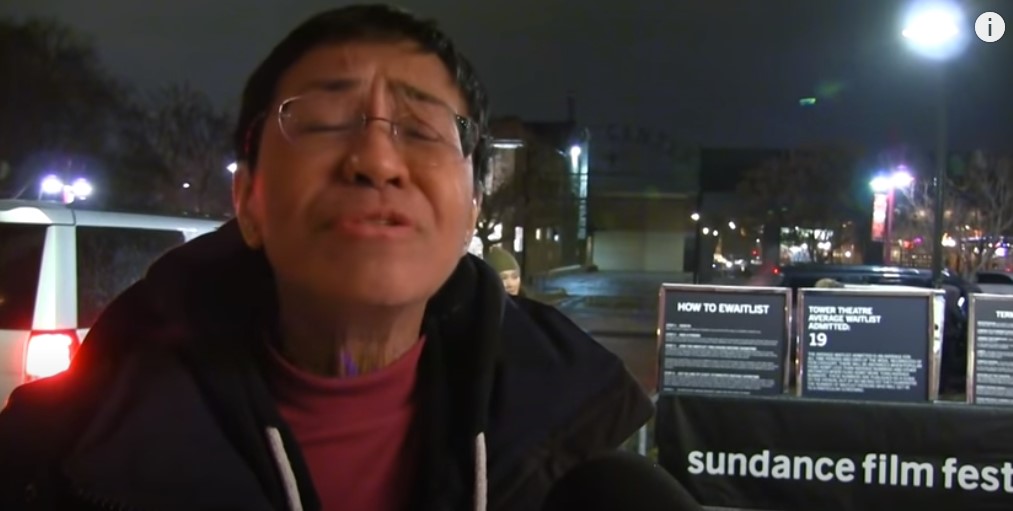

That Maria Ressa for all her “sacrifices” has been crowned martyr and heroine deserving of a Sundance movie and a Time Magazine canonization — can only be the work of creative marketing genius and persuasive foreign financing.

The movie is foreign-funded. Rappler itself is foreign funded. Ressa even proudly proclaims this fact.

Accepting foreign funding is not illegal, they retort. Even if the foreign funding comes from the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), which is reputed to be a CIA front.

I cannot imagine Ditto, Joe or Max soiling their reputations by soliciting funding from suspected CIA conduits.

And that is the tragi-comedy that is Rappler.

It is NOT an independent media machine fueled by the people’s rage against government abuse.

It is a foreign funded corporate brand that seeks to market its commodity (“fighting for a free press in the Philippines”) to generate foreign sympathy (commercial demand) and attract financial patronage (commercial purchase). The marketing objective is to make the consumer (foreign funder) feel the consumer satisfaction of having contributed to what appears like a noble cause.

Rappler’s content is narrowly tailored toward that foreign market and styled to support that contrived marketing narrative.

In contrast, the alternative press fighting against Marcos had none of that marketing gloss, but it had genuine popular support. The narration of the Center for Media Ethics and Responsibility reads:

“Despite its small and meager funding, WE Forum [and later, Malaya] survived because of the support it got from a vast, spontaneous network of concerned Filipinos. Teachers and professionals donated office supplies; conscience-stricken bureaucrats supplied Burgos with an endless stream of stories—from simple tip-offs on the latest, hottest administration scandals and the shopping sprees of Imelda Marcos, to documents and technical data on government irregularities.”

That you have to resort to a marketing blitz should speak volumes about the authenticity of your cause. The irony is, among her own fellow Filipinos (assuming even that she is one), Ressa’s stature may not even rise to the level of that Youtube comedy sensation known as Francis Leo Marcos.

The comparison is not forced.

Ressa and FLM both have appealing but deceptive narratives. “Philippine journalists are under attack. I am being persecuted,” says one. “I am crazy rich but I am helping the poor,” says the other.

One is the darling of the foreign elite and out-of-power politicians . The other is the matinee idol of the low-income multitudes longing for a local Robin Hood with a sense of humor.

While both are marketing gimmicks, the difference is in the degree of sophistication.

Which perhaps explains why one is not yet in jail, while the other is already there.

(Credit to Atty. Alexis Medina, lawyer and film critic).